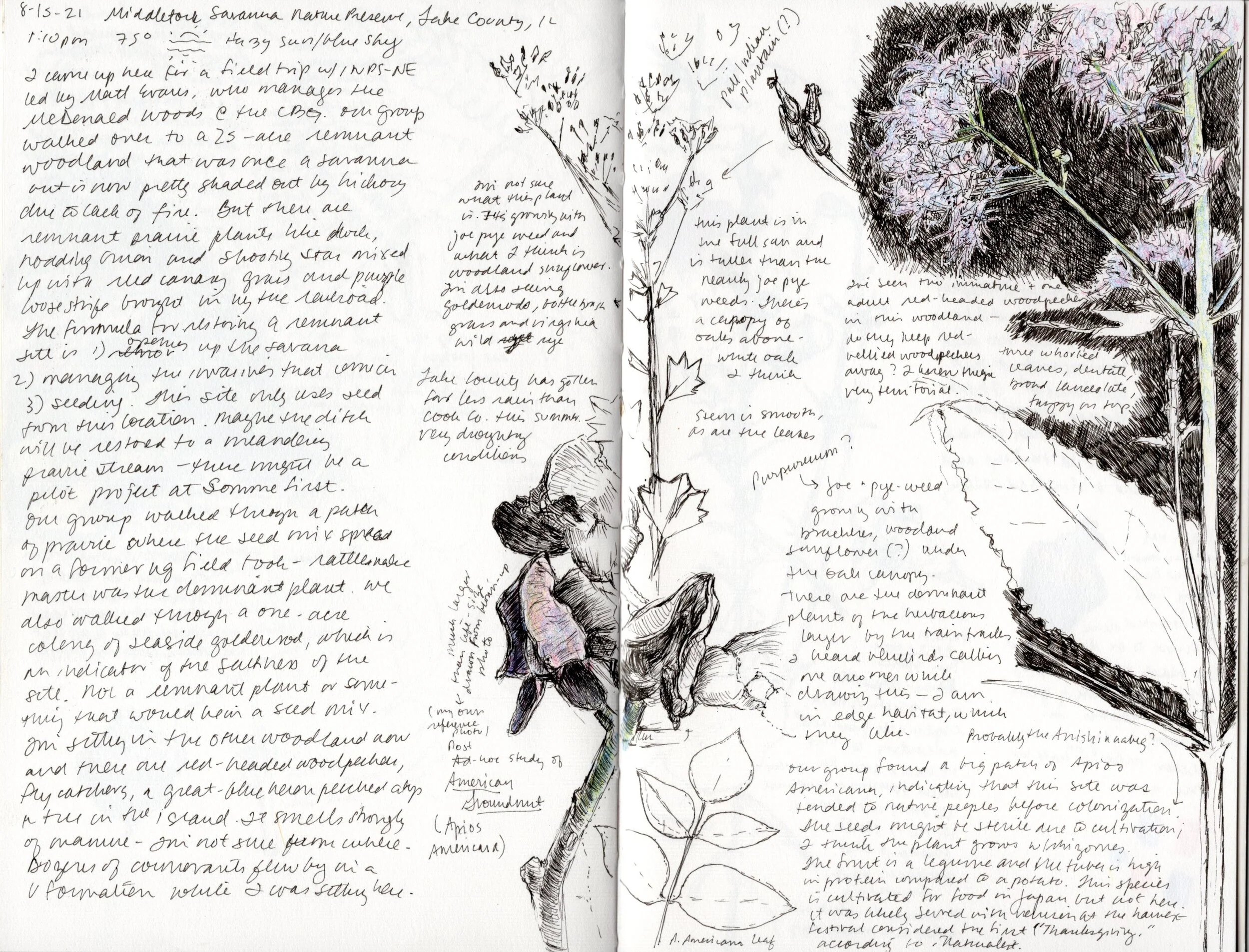

I’ve encountered this intriguing and elegant legume flowering on recent visits to Middlefork Savanna in Lake County, north of Chicago, and the Indiana Dunes National Park. If you live in the eastern part of what is today called North America, you can probably find it growing somewhere near you.

Among the common names for this plant in English is Ground Nut, and its Latin name is Apios americana. There are many more names for it in the languages spoken by the peoples indigenous to the eastern portion of what is now called North America. These names include mûkwópinik, as spoken by the Anishinaabeg First Nations concentrated around the Great Lakes region where I live.

Last November, I learned during a presentation by Frank Barker, a Gun Lake Potawatomi Tribal Citizen, the difference between English, Latin and Indigenous forms of language in the context of science. English uses nouns to categorize things, while Latin binomial nomenclature is used for universal understanding. Indigenous languages, meanwhile, use descriptive words of plants and their relationships with other living beings.

For example, in English we have Yellow Birch (a birch which is yellow); in Latin, Betula lutea (family/species); in Bodewadomi (Potawatomi): Winsatik (he smells like the woods). For Common milkweed, the Latin is Asclepias syriaca and in Bodewadomi it’s Nenwesh or “man plant,” in that people can use the plant in many ways — the plant was made for us to help us take care of ourselves. Frank said that when we think of things like plants as being inanimate — as being nouns or objects that can be possessed, rather than as a way of being and relating — it’s easy to be more uncaring and destructive of them.

The tubers of mûkwópinik (there’s a brief mention of a translation of this term as “bear potato” in a 1999 essay by botanist Ray Schulenberg) were a staple food of Indigenous peoples who cut them to propagate it (the beans it produces are edible for people too). According to iNaturalist, “The groundnut was likely eaten at the harvest festival of November 1621 that is regarded as the first Thanksgiving.” The tubers likely helped early European settlers avoid starvation, as pilgrims were taught to dig up and cook groundnut by the native Wampanoags (see “Stalking the Wild Groundnut” by Tamara Dean in Orion Magazine).

(I also encourage you to read this 1970 speech by the late Wamsutta Frank James, a Wampanoag man who had been invited to speak at a state dinner at Plymouth, Massachusetts, celebrating the 350th anniversary of the pilgrims’ invasion of Wampanoag territory. Wamsutta was prevented from delivering his speech when it was read in advance by the event organizers, who wanted him to say what the pilgrims’ descendants wanted to hear, which he refused to do. Wamsutta founded the National Day of Mourning that year, and it has been marked annually ever since on the settler holiday of Thanksgiving, led by the United American Indians of New England. There’s a great interview with Kimimila Sa (Kisha) James, Wamsutta’s granddaughter, and Mahtowin Munro on the Red Nation podcast debunking pilgrim mythology around the holiday and discussing the purpose of the National Day of Mourning.)

A flowering American Groundnut that I found at the Indiana Dunes National Park.

I learned during a field trip to Middlefork with the Illinois Native Plant Society that the presence of this plant in substantial numbers, as was occurring at a remnant savanna on the site, suggests that the location may have been a place where it was propagated by Indigenous people prior to colonization.

“Chicago,” where I live, comes from the Bodewadomi word for wild ramps, another native plant. Though I grew up in the suburbs of this modern metropolis named for a native plant, I learned nothing of the ecology of the land where I lived, and from which my family’s middle-class wealth was derived, until very recently.

I certainly didn’t grow up learning anything about the peoples who called this place home before Euro-American colonization robbed them of their land and way of life. I know in broad strokes now that they played a key role in shaping the ecology of the landscape through their cultural, agricultural and hunting practices after the glaciers retreated more than 11,000 years ago.

Though Illinois is called the Prairie State, the millions of acres of grassland once found here was destroyed in a matter of decades with the invention of the mechanical plow. (Incidentally or not, multiple members of my family worked for a manufacturer of farming equipment during the second half of the last century.) The acreage of remnant prairie in Illinois today is smaller than the footprint of O’Hare airport. This too I learned only in the last few years.

There’s probably a reason why I wasn’t taught these things in school.

Understanding our local ecology would compel us to change our cultural attitude towards land from one of ownership and profit extraction to one of reciprocity and caretaking. Learning about and respecting the peoples native to this land would mean reckoning with colonialism’s brutal history of genocidal violence and dispossession. Those invested in upholding the current system of capitalism — towards which colonization remains an ongoing process — would not countenance either of these fundamental cultural shifts, as it has not countenanced reparations for the labor stolen to build the wealth of this country via chattel slavery.

I often think about this passage from Joel Greenberg’s A Natural History of the Chicago Region, describing a site in the town I grew up in:

Several years after these two biologists [Henry Gleason and Victor Shelford] declared that Illinois’ prairie was gone, Arthur Vestal published the first scientific study of a Chicago area prairie. Known as Elmhurst Prairie, the site had been left alone by virtue of its small size and surrounding forest and marsh. Composed of mesic and wet prairie, it provided habitat for such conservative species as Hill’s thistle (Cirsium hilli), Indian paintbrush (Castilleja coccinea) and prairie milkweed. If, as we shall see, the Great Depression saved the prairies of Markham and Westchester, the affluence of the 1950s decreed the death of Elmhurst Prairie. Slashed and scraped by blades of the Tollway Authority in 1957, it lies interred under Route 294, a loss now barely remembered (p. 47)

Through this anecdote, I can start to connect my family’s middle-class prosperity to the destruction of the natural landscape. For me, making these connections does not generate feelings of guilt, but instead a feeling of responsibility to begin these relationships less wrong, and a feeling of optimism that things can be much better than they are at present for all living beings. Driven by my curiosity, these connections also make history less abstract and help me begin to overcome the alienation from place encouraged by settler-colonialism, instilling in me a deeper connection to this landscape. These are ideas I hope to explore more thoroughly as I strengthen my relationship with this land and all the history (and futurity) that’s wrapped up in it.

But back to the vining legume that inspired all these lines of inquiry: The presence of mûkwópinik may indicate a cultural history that the processes of colonization have sought to erase. Learning to recognize this plant and the habitats that it grows in, and inferring the histories they may reflect, is a small but meaningful step towards cultivating place and shifting our culture away from alienation and towards connection: to our environment and our obligations to care for the land and one another.

(Disclaimer: I am not an expert on ethnobotany or any of the other themes I discuss here. This blog is where I think on virtual paper and share my learning process with others. I may get things wrong. Any additional information, suggested further reading, corrections and critiques are welcomed and encouraged.)

Sources:

Flora of the Chicago Region by Gerould Wilhelm and Laura Rericha

A Natural History of the Chicago Region by Joel Greenberg

“Stalking the Wild Groundnut” by Tamara Dean, Orion Magazine

American Groundnut, iNaturalist