What is nature journaling?

Here’s a definition from Paula Peeters:

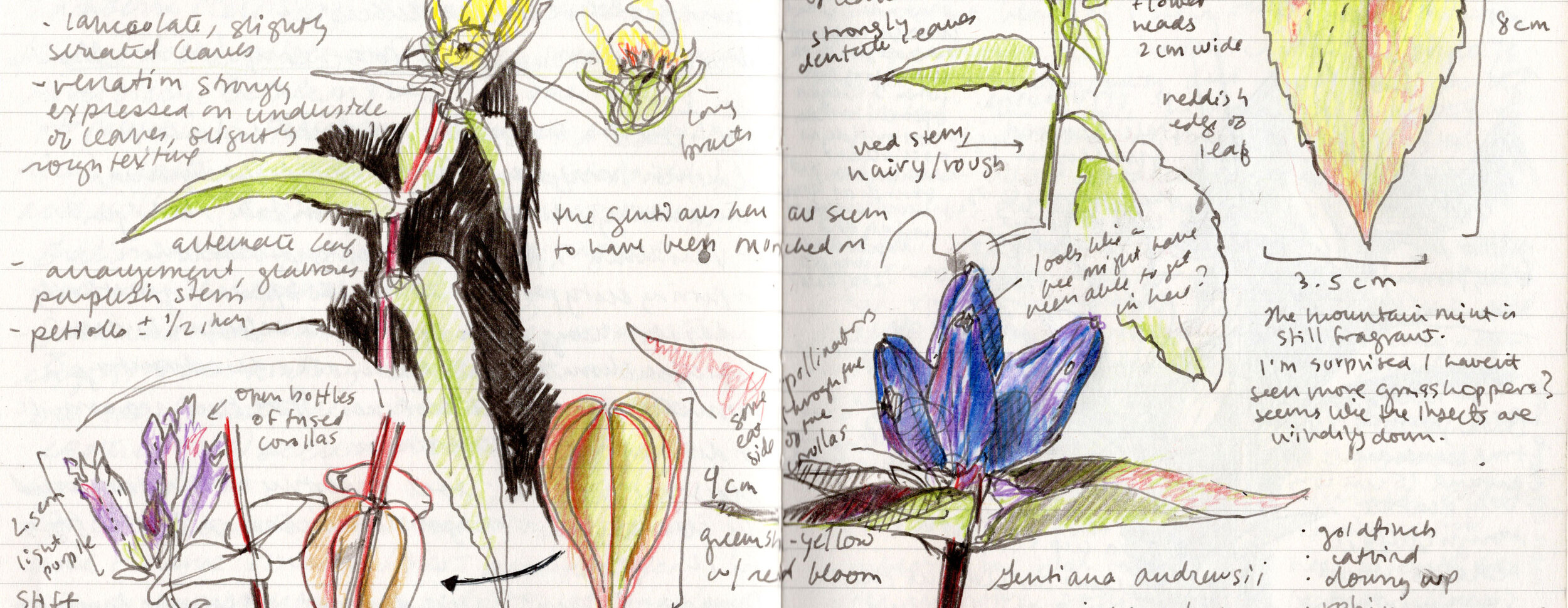

“Nature journaling is the practice of drawing or writing in response to observations of nature. This practice results in the creation of your own unique nature journal. ... It helps you to notice the details in nature, and improves your recognition of different species, and your understanding of where and how they live.”

Nature journaling isn’t so much about writing and drawing. It’s more about seeing and observing. It’s a means by which we can slow down, deepen our connection to our environments and better appreciate the astounding diversity of life all around us. Through this connection, we can find our own sense of place.

Nature journaling is a practice. Deep observation is like any other skill -- it must be practiced and developed. With practice, I’m sure you will find that the quality of your nature journal observations will strengthen over time. And a regular practice of deep observation will change the way you see and relate to the world.

To me, the purpose of nature journaling is not to make a beautiful picture or a perfect poem. It’s to commune with more-than-human life and foster sustained and compassionate attention to the world around me. Nature journaling may help calm any anxiety you may be feeling and leave you feeling more refreshed than before.

How do I start nature journaling?

Grab some paper and a writing utensil

Find an interesting aspect of nature to observe

Start journaling, using a combination of words, pictures and numbers

Those are the bones of nature journaling. And your journaling practice doesn’t even have to be on paper. It could be done through audio or video media; it’s really the principles of observation that matter. But I journal using a traditional book format, so that’s what I’ll be elaborating on here.

What materials should I use?

Your sketchbook or notebook doesn’t have to be anything fancy, and something fancy may be intimidating for anyone just starting. The best journaling surface is the one that you’ll actually use. And the same principle applies to your writing/drawing implement. Over time you might want to experiment with other media. But your nature journal can be as simple as a composition notebook and a ballpoint pen. Keeping it simple will encourage you to carry your journal around with you so that you’ll actually use it.

If you’re on a hike or you set out somewhere with the intention of nature journaling, open your journal as soon as you get to your destination. Write down the location at the top of the page and the date and time, the weather conditions, and any other pertinent metadata. Take a few moments to record your first impressions or whatever is on your mind. Tap into your senses. What are you feeling at the moment? Write it down or represent it through images in your journal. Holding your journal in your hand and getting some first marks or words on paper will establish your intention and encourage you to record more observations while you’re there.

What should I observe?

You can nature journal about pretty much anything from pretty much anywhere. This is both wonderful and potentially overwhelming.

Consider starting with small subjects. Instead of journaling a whole tree, try focusing on buds, a fruit, a seed, or an individual leaf. (If you find a fairly flat leaf, you can even trace it.)

During cold winter months, I like to walk to one of the community gardens in my neighborhood and observe dormant plants. Or I go to the lake and observe gulls congregated on the beach. Trees offer us something to study and appreciate year-round: buds, bark, leaves, seeds, and evidence of other organisms' activity on any of their parts. Here in Chicago, there are always Canada geese and house sparrows around, and squirrels too. They frequently appear in my nature journal.

Sometimes I nature journal from inside my home. I can observe birds from my window and describe their behavior in my journal. Some nature journalists will study the same thing over time: like a germinating avocado seed or changing light and weather patterns in the sky, viewed from one of your windows. You can also find a nature journal study subject in the crisper drawer in your fridge.

Sometimes I have a subject in mind when I set out to nature journal. Sometimes that aspiration can be as non-profound as I’m interested in flowers with umbel-shaped inflorescences because I like the way they look, so I want to focus on them in my journaling for the day. Sometimes I’m looking for a particular plant species because I know from experience that it’s flowering that time of year, and so that will be a nature journaling target for the day. But most of the time, I just set out with the intention of putting something on the page and respond to whatever sparks my curiosity that day.

How do I observe?

Following your curiosity is the mindset of nature journaling.

John Muir Laws offers three prompts that can shift our mindset to one of curiosity:

I notice

I wonder

It reminds me of

If you’re ever feeling stuck or need a gentle nudge, these prompts can fuel unlimited exploration of whatever you are observing. You can practice these prompts right now! John Muir Laws leads you through them in this video:

Here’s the breakdown of what Laws says, starting with our first prompt:

“I notice …”

This prompt invites us to take a closer look at our subject. Laws encourages us to say our observations out loud. Look at your subject from multiple angles and consider its shape, structure, color, texture, smell and sounds, take note of any damaged parts or behavior. You can also consider the other living things (or otherwise) in your subject’s environment.

If you feel stuck, just keep saying “I notice” out loud and the observations will come.

Now let’s move on to our second nature journaling prompt:

“I wonder …”

This prompts gets us more curious about whatever it is that we’re looking at and start asking questions like:

Who, what, where, when, how, why?

Why is it like this?

How does it work?

how or why is it changing?

How is it connected to other things?

Are there patterns here?

Sometimes these “I wonder” questions will come easily. Sometimes you’ll have to give them some encouragement; “Who, what, where, when, how, why?” are great questions to keep in your back pocket.

As Laws explains, our first questions are often not the most interesting ones. But you have to ask those questions first to get to the more intriguing ones that follow.

The purpose of the “I wonder” prompt isn’t necessarily to answer our questions, but to shift our mindset to a more expansive one of curiosity. So you may be observing a Northern Cardinal, a common bird in Chicago that is easy to ID. “I wonder” encourages us to go beyond the ID and give that cardinal greater attention, which may yield unexpected rewards.

And now on to our third and final nature essential journaling prompt:

“It reminds me of …”

With this prompt, we make connections between whatever it is we’re observing and other things we have seen, experienced or learned.

As Laws explains, embedded in your “It reminds me ofs” are compelling ideas and connections between your subject and other things we have seen or experienced. This prompts us to ask more questions and make more observations.

No connection is too obvious or too frivolous — let your mind roam freely!

So now that we’ve established how we can get into the mindset of nature journaling, let’s consider the tools we have to transfer the observations we’ve made and document them on our nature journal pages.

For this, we have three languages, if you will, that we can use in combination with one another to communicate and document our observations. These three languages are words, pictures and numbers, to be used in whatever way suits you.

Once again, I’ll be summarizing the teachings of John Muir Laws, who gives an overview of these nature journaling languages in the video above.

Our first nature journaling language is that of written words.

As Laws explains, using words in our journal allows us to be very specific and hone in on any details we may wish to record. They can describe our questions and any explanations we may have, which might be difficult to illustrate in a picture.

And that leads us to our second language, which is that of pictures or illustrations.

As Laws explains, “When we're putting pictures and drawings in our journal, the way our brain works is fundamentally different from the way it works when we're just writing with words.”

Pictures are not better than words, or vice versa, “but they exercise different parts of our brains. When we're intentionally using words and we're intentionally using pictures in our journal, we have more of our brain to play with for whatever it is that we're observing.”

The purpose of using pictures in our nature journal is not to make a pretty picture, though you may end up with one. The goal here is for our pictures to be useful, to serve as a visual strategy to describe our subject.

Pictures can include a map, a simplified diagram, a visualization of a bird’s song, or a portrait of a flower. Pictures can be zoomed in or zoomed out, show the subject from multiple angles.

If making a picture sounds intimidating to you, consider starting with something relatively two-dimensional like a leaf that you can trace.

And now on to our third and last nature journaling language, which is numbers.

As Laws explains, “If we start counting, measuring, timing and finding numbers in the phenomena we observe, this trains us to be really specific in another kind of way.”

A really easy way of getting some numbers onto your page is to make a note of the date and time at the top of your page, and if you’re journaling outdoors, the temperature. More ways to incorporate numbers onto your page would be to count the number of chambers in a seed pod, for example, or estimate the number of seeds contained in one of the chambers; it could be the number of petals on a flower; the number of house sparrows gathered at your feeder; the number of seconds a chickadee stays on your feeder before flying off; the number of seconds a merganser stays under water before resurfacing.

Using these three languages in combination with the “I notice, I wonder, This reminds me of” prompts are a powerful way to look at the observe, document what you find and make new and exciting connections.

Am I doing it right?

If you have a moment of doubt, remember that you’re not doing it wrong. You’re doing it your way.

I was once told that the only way to do field sketching wrong is to not do it at all. The same applies to nature journaling.

We live in a culture that asks us to optimize everything. We’re expected to master everything we do; we’re repeatedly given the message that we should only do something unless we can excel at it, be the best at it, or make money from it. Nature journaling is the antithesis of and an antidote to this social messaging that discourages personal growth.

Nature journaling is a deeply personal practice. You don’t have to share your pages with anyone, though this can be rewarding in a supportive community of other nature journalists.

Looking at other people’s nature journal pages on social media can be discouraging. Try to stay focused on your own journey and avoid comparing what you do with what other people do, unless you want to learn from their technique, method of observation, or what kind of tools they use.

There are plenty of generous nature journalists out there who use their platforms to share their techniques and experiences with the aim of getting other people excited about nature journaling (it’s a practice that encourages generosity). For more on this, see “Where can I learn more?” below.

What gear should I use?

You can start nature journaling with what you already have. Your nature journal kit can be as simple as a composition notebook and a ballpoint pen.

My current nature journaling kit includes a Stillman & Birn Epsilon series wire-bound sketchbook (I have a smaller hardcover one too). I like these because they work well with pen and ink and can handle a light wash. Someone who uses watercolor might like a different type of paper, and someone who just uses a ballpoint pen won’t necessarily need such a high-quality paper. Whatever you end up using, I recommend using something with a stiff cover. Having a bulldog clip or two in your nature journaling kit is handy to keep your pages in place if you’re journaling in a windy environment.

As for writing and drawing implements, I’ve been keeping it simple (by my maximalist standards, at least) and usually just carry a pen with walnut-colored ink, another pen with gray ink (I have been using inexpensive Platinum Preppy fountain pens; when you use up the ink cartridge the pen comes with, you can use a syringe to fill it with any bottled ink you like). I also typically have in my kit couple of inexpensive water-soluble pens that you can get at an office supply store. I also like really fine-lined Micron pens, in brown and black ink.

Another essential tool in my kit is a waterbrush. This is a nylon-bristled brush with a built-in water reservoir. It’s tidy and extremely handy for doing washes in my journal.

In the wintertime, when it’s really cold and I therefore work fast in my journal, I pretty much just use pen and ink. But when conditions allow for more time outside, I might include in my kit a limited palette of Faber-Castell watercolor pencils (not so inexpensive). I like botanical artist Wendy Hollender’s 13-color palette. I’ll often carry the same palette of Faber-Castell Polychromos pencils. A white plastic eraser and pencil sharpener are good to have if you’re using pencils in the field.

I always have a T-shirt rag in my bag in case I need to lift a wash or need to blot something.

I also typically have a small ruler, a hand lens and these compact and very lightweight binoculars that are great for examining something up close and for seeing things far away.

I carry all of this in a Tom Bihn Maker’s Bag. These are not cheap. You really don’t need a fancy bag to nature journal. I got this one because of the quality of manufacturing and because it can hold all my nature journaling stuff plus my coffee thermos or a water bottle and a field guide. I don’t have a car and get everywhere by public transit or bicycle, so I need to be able to carry everything on me when I’m out in the field. My one gripe about this bag is that it’s kind of a struggle to get my 9x12 sketchbook in and out of the full bag. I wish it had a big outside pocket on the back to make it easy to grab my sketchbook and put it back when I’m in the field. I do recommend a shoulder or messenger-style bag versus a backpack, because the easier it is to grab your journal, the more likely you are to use it.

Where can I learn more?

Here are some of the resources I’ve consulted along the way during my nature journaling journey:

Books:

Nature Drawing by Clare Walker Leslie

The Art of Field Sketching by Clare Walker Leslie

The Laws Guide to Nature Drawing and Journaling by John Muir Laws

How to Teach Nature Journaling by John Muir Laws and Emilie Lygren

Artist’s Journal Workshop by Cathy Johnson

Botany for the Artist by Sarah Simblet

Botanical Drawing in Color by Wendy Hollender

Websites:

Marley Peifer (I’ve especially appreciated his YouTube videos, some of which include interviews with nature journalists)

Julia Bausenhardt (she also has several classes on Skillshare)

Bethan Burton’s Journaling with Nature

Podcasts:

The Journaling with Nature podcast hosted by Bethan Burton. Each episode features a long-form interview with a different nature journalist. Each episode is a calming breath of fresh air.

Classes:

I’ve also taken several classes in the Chicago Botanic Garden’s Botanical Arts certificate program, all of which were excellent. If you’re able to take any of those classes, I’d highly recommend them.